So to start off with we need to make sure that we’re clear on what covalent compounds are, and how they differ from ionic and metallic compounds. If we think about the definitions we have used thus far (I realise that everyone will have used different words to say these, but the ideas will be the same) they will help us here:

Ionic bonding – involves electrons being given from one of the atoms to the other to form ions (positively and negatively charged atoms) which are electrostatically attracted to each other (the bond).

Covalent bonding – electrons are shared between the atoms forming the bond.

Metallic bonding – the atoms involved in the metal give up one or more electrons forming positive ions which are help together through attractions to the negative electrons which form the “sea of electrons”.

We are only going to consider covalently bonded (purely or largely) compounds. Purely covalently bonded compounds are found to occur between two atoms with little to no difference in electronegativity between then.

As an aside – remember that electronegativity is a measure of how much an atom pulls an electron towards it with in a bond. If you have two atoms with the same electronegativity, i.e. if you have two of the same atom, the electrons will be equally shared between the atoms. If one of the atoms has a greater electronegativity value than the atom to which it is bonded, the electrons will be pulled towards the more electronegative atom, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Showing the electrons a) in the centre between two atoms of equal electron density and b) being pulled towards the more electronegative atom A.

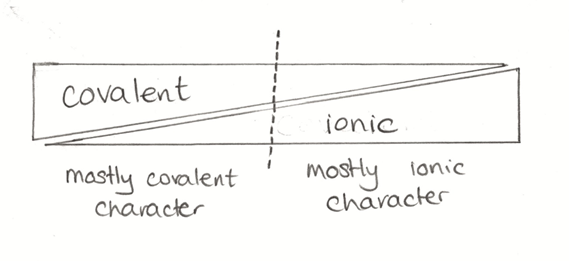

Compounds such as H2, N2 and CH4, are largely covalent, but some, such as H2O and CO, have ionic character as well. We can think of the degree of covalent and ionic character to a bond varying as shown in Figure 2. We tend to treat things on the left hand side as covalent and those on the right as ionic, but we should remember that this is, normally, a simplification.

Figure 2. Diagrammatic representation of how the degree of covalency and ionicity varies.

Revisiting Orbitals

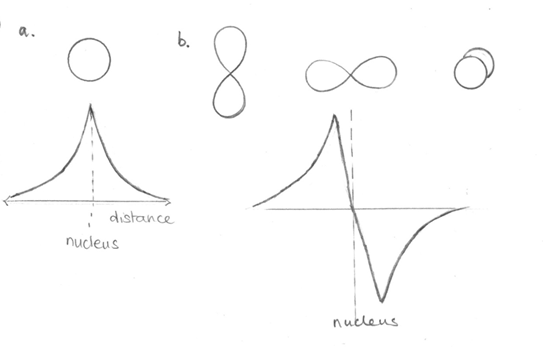

We have already thought a bit about orbitals, and here again this is important. We have to be able to picture the orbitals involved in the bonds we are looking at as this will help us explain how the bonding occurs. So just to remind ourselves we need to remember that s-orbitals are spherical and come singly, and p-orbitals are dumbbell shaped and come in threes (see Figure3). It will also be helpful to be able to think about the different phases of the orbitals. Here, again shown in Figure3, anything above the x axis on the graph is defined as positive and anything below this axis as negative. Thinking of it like this will help when we look at adding the orbitals together.

Figure 3. Showing the shape of the s- and p- orbitals and below this the cut through the orbital showing the change in phase for the p-orbital.