Introduction: What do you think of when you think of translation?

When we think about translation, we tend to think of the wealth of cultural works of fiction we now have access to thanks to the work of translators and interpreters. In an increasingly globalised society, English-language media no longer exclusively dominates the English-speaking market. For instance, you may have recently enjoyed Netflix’s Spanish-language series Casa de papel (known as Money Heist in its English-language dub), or you could be one of the countless number of British young people learning the lyrics to your favourite K-pop songs from English-language translations. And you wouldn’t be alone in your consumption of foreign-language media. A 2014 BFI survey estimated almost half of British people have seen at least one foreign-language film in the last 12 months on any platform. There’s no denying the impact translators have in the world of arts and culture.

However, this is not the only role translation plays in our lives. Translators and interpreters play a vital role in helping us understand real-life events taking place outside of the English-language world. You will likely have seen, for instance, news reports from warzones which use interpreters to translate the testimony of people displaced from their homes who do not speak English. You may also be aware of how translators have assisted in criminal proceedings, often conveying crucial witness statements across the boundaries of language and culture. In such cases, providing a reliable, accurate translation of often-sensitive information means translators have to work incredibly carefully, equip themselves with a thorough, culture-specific knowledge and avoid bias.

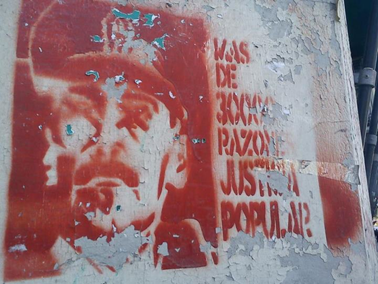

Graffiti in Buenos Aires calling for those implicated in Operation Condor to be brought to justice

Translation as truth-telling: “lo indecible” in post-dictatorship Latin America

Exactly how difficult is to translate personal testimony when this material itself is difficult to access? The gatekeeping of memory (and the subsequent impossibility of accessing the source language resources we need as translators) is often beyond our control. In such cases, the voices of the disempowered are often suppressed, justice is not served, and translation cannot be used to its full purpose; as a necessary tool for exposing truths we would not have otherwise been made aware of.

One such example of repressed truths we can draw upon is the long path to justice faced by people in many South American countries following their transition to democracy in the latter half of the twentieth century. During the mid-1970s, the United States backed a campaign of political terror in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. The aim of the operation, which was given the moniker Operation Condor, was to suppress left-wing sympathisers. This was achieved through installing right-wing dictators across the continent and kidnapping, murdering, or otherwise “disappearing” opponents to the regime.

In Argentina, a military junta deposed then-President Juan Perón and installed General Jorge Rafael Videla as leader of the country. During Videla’s eight years as head of government, historians estimate somewhere in the region of 30,000 Argentine dissidents were kidnapped, tortured and murdered. Children were taken from their families and sold into families abroad, many never to be seen again. It wasn’t until 1985, after the end of the so-called “Guerra Sucia”, or Dirty War, that trials took place to hold those responsible to account. However, owing to fears of another coup, the trials were quickly stopped and didn’t recommence until 2003. In the meantime, every Thursday a group of women known as the Madres de Plaza de Mayo met in front of Buenos Aires’ Casa Rosada (the seat of power in Argentina) to demand answers as to what became of the children they had forcibly removed from them. Even today, many still do not know what became of their loved ones, and some feel that there has still been no true justice.

How does this relate to political translation? Well, it is an example of a complicated, real-world scenario in which truth has been suppressed, and anyone involved in translating the accounts must tread carefully. Many of those who suffered under Videla’s regime are still alive, and the issue of whether or not justice has been served is a contentious one. Translators must work delicately, and ensure they have a good grounding in the historical context of their work in order to accurately and sensitively convey the meaning into the target language. In the attached worksheets, you will be able to tackle both written and oral testimonies relating to those directly implicated in the Guerra Sucia. Bear in mind the history of the texts when working on your translations.

Speaking tongues: how to translate different varieties of language

Of course, translating politically charged material doesn’t just rely on cultural context to ensure accuracy. The way language is spoken often differentiates the oral testimony of someone’s experiences from, for instance, courtroom proceedings or official reports. This ranges from the lexical choices employed, to subtle grammatical differences not entirely obvious to a non-native speaker. If you’ve studied Spanish (or indeed any Romance language) before, you may be familiar with the difference between the informal “tú” and the polite “usted”. These differences in grammatical person are largely untranslatable into English but connote an entirely different register; their presence in the text would mean your translation would have to be adjusted accordingly. Returning to our Argentine context, the attached video resource will introduce to more linguistic variation unique to Argentine Spanish, including a further grammatical person you may be unfamiliar with; the “vos” form, known as the voseo. Keep them in mind when working on the activity resources, and consider how regional variation might influence your translations in other areas and languages.

“El Caminito” in Buenos Aires’ vibrant La Boca district

Finally, how loosely you choose to interpret your source material is crucial to any translation and is almost entirely dependent on context. Official documents, for example, must closely follow their source and avoid deviating too much for fear of giving rise to legal misunderstanding, whereas translations of fiction and some journalistic writing can allow their translator some creative flexibility. Translators must additionally weigh up between domestication and foreignisation, two terms debated for hundreds of years but best termed in modern times by a translation theorist called Lawrence Venuti. Domestication refers to opting for a translation which doesn’t challenge the reader to consider “foreign” concepts; this may include, for instance, substituting foreign brands from the source text for ones more familiar to UK readers. Foreignisation, on the other hands, favours retaining the text’s foreign individualities to maintain a sense of the culture from which it emanates. Venuti is a vocal opponent of domestication, but that doesn’t mean you have to be. When translating any politically sensitive text, evaluate how necessary it is to stick to your source – if your aim is to convey an otherwise repressed truth, as in the case of the victims of Videla’s dictatorship, could deviating too much betray this truth?